WHAT IS NÉGRITUDE?!

If you've explored our site, you may have noticed the word "NEGRITUDE" embroidered in vibrant red, black, and green—the Pan-African colors—on the sleeves of our MeWe tees and hoodies.

This is no coincidence. For years, our founder, Ryan K. Smith, has signed off on social media as “Yours in Negritude, Ryan K. Smith,” a tagline that reflects his deep connection to this revolutionary movement.

What follows is an explainer on the history and philosophy of Négritude, presented by Carneades.org on YouTube. This blog post dives into the roots and evolution of a movement that shaped Black identity, pride, and resistance in the 20th century. From the poetic expressions of Aimé Césaire and Léon Gontran Damas to the philosophical framework of Léopold Sédar Senghor, Négritude has stood as a rallying cry for Black affirmation and unity against colonial oppression and anti-Blackness.

NÉGRITUDE THE MOVEMENT

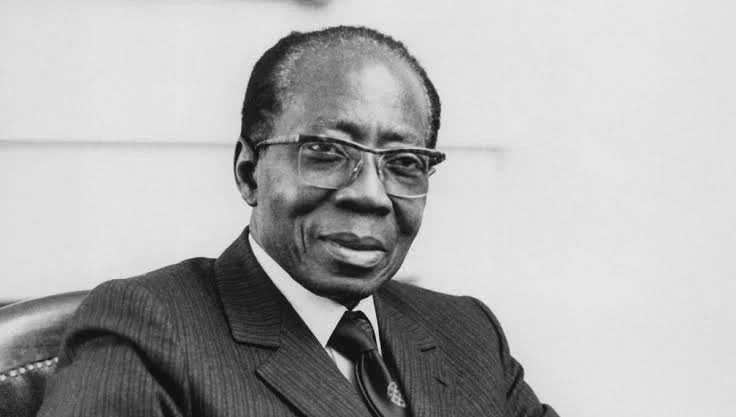

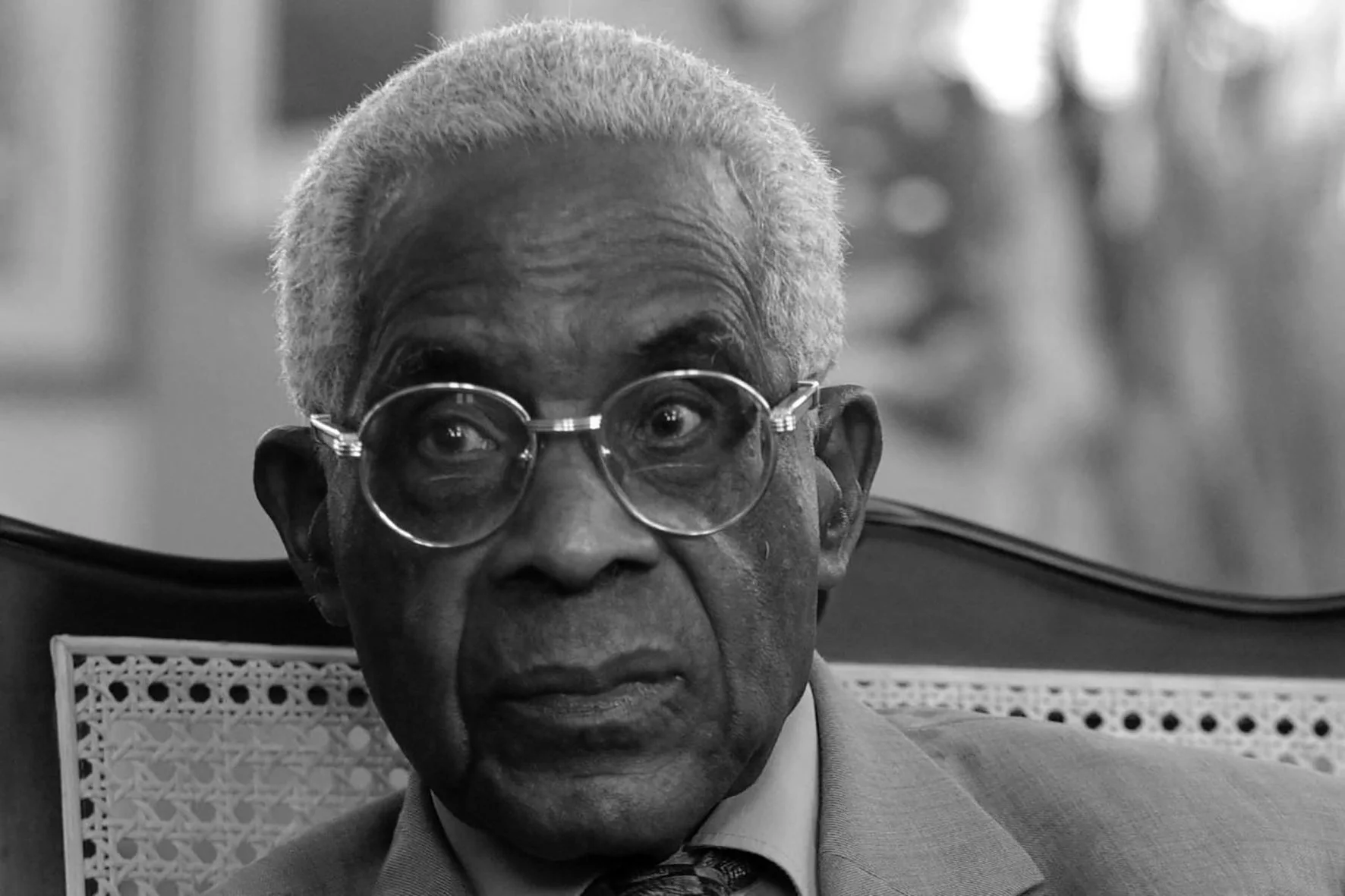

Négritude is a philosophical, poetic, and political movement most closely associated with Leopold Sedar Senghor, Aime Cesaire, and Leon Gontron Damas. The movement focuses on the affirmation and valuation of Black people and Black experiences in the world. Cesaire and Damas viewed Négritude more as a poetic movement while Senghor enunciated more philosophical content of the movement.

Leopold Sedar Senghor (CREDIT:: Getty - Erling Mandelmann/Gamma-Rapho)

Aime Cesaire (CREDIT: Bazar do Tempo)

Leon Gontron Damas (CREDIT: Black Past/Ajuan Mance)

Négritude has its origins in a meeting and shared experience of Cesaire from Martinique, Damas from Guyana and Senghor from Senegal in Paris. They shared their common experiences of French colonialism and anti-blackness, which according to Cesaire, led the people of Martinique to attempt to distance themselves from their African ancestry and adopt European values and ideals. So there was this problem of the devaluation of blackness leading to individuals in these cultures to internalize the racism and think that their connection to their African heritage was a bad thing. So out of this common experience of oppression, they built together a movement centered around both the shared experience of people of African descent living in a world dominated by European ideals and cultures, but also a valuation and valorization of blackness as a unifying cultural identity to be proud of. According to Cesaire, Négritude attempts to answer not Descartes' question of who am I as a human, but the question of who are we as a Black people in a white world?

An important influencer of Négritude was the exposure of Demas, Senghor and Cesaire to the works of the Harlem Renaissance and the Haitian Renaissance in the salon of three sisters, Jane, Paulette, and Andree Nardal. They encountered wordsmiths like Langston Hughes and Claude McKay, and found both cultural commonalities distinct from French colonialism and the shared expression of Black pride and cultural identity. Négritude was for Cesaire and Demas, a movement of poetic revolt, fighting oppression with artistic expression of the lived experience of Black people. The movement provided a space for Black people to tell their own stories and create their own art independent of racist narratives about them.

This poetic revolt Included the term Négritude itself, which was based on a reclamation and reappropriation of a French slur for Black people. This is emblematic of the poetry which fought to redescribe the Black experience of colonialism, slavery, and Black identity from the perspective of Black people themselves. While Sanghor's works included anthologies of such revolutionary poems, he also espoused a specific philosophy of Négritude (which will be covered later).

One reason that Négritude needed a more philosophical expression was that without one, it was in danger of being defined by others. Specifically, the movement gained wide attention following Jean Paul Satre's preface 'Black Orpheus' for Senghor's ‘Anthologie de la Nouvelle Poesie Negre et Malgache de Langue Francaise.’ Satre's preface is often treated as the 'kiss of death' for Négritude, as it both popularized the movement while simultaneously defining it into obscurity as merely a step on the way to a post-racial society. So to understand this, let's dig in a little bit to black Orpheus and the controversy surrounding it.

Satre highlighted many of the virtues of the Négritude movement, identifying the reappropriation of the language of the colonizers to break European connections between goodness and beauty and whiteness. He claims that these poems achieve the surrealist goal of breaking the cultural associations by expressing the beauty and goodness of Blackness and the Black experience. In this way, Sartre showed that there was something philosophical and not merely poetic to the movement and therefore popularized it. However, Sartre saw this movement as only an intermediate step towards the goal of a post-racial society. Satre framed ude in terms of his understanding of a Hegelian thesis, antithesis synthesis dialectic. For the uninitiated, this theory simply states that progress is made throughout history by the introduction of a thesis, a positive viewpoint followed by an antithesis, the opposing negative viewpoint, and finally, a synthesis of those viewpoints which resolves the dispute.

For Sartre, Négritude represented the antithesis to the thesis of white supremacy. Sartre characterizes it as an anti-racist racism. For Sartre, this was merely a step on the path to a post-racial synthesis. As a Marxist, Sartre argues that race is merely a subjective concrete, particular to use Heider's language, while class is the only true universal abstract, and for synthesis to occur, racial identity must be shed. In doing so, Satre denies one of the central elements of Négritude, that there is a uniquely and essentially universal Black experience. By defining Négritude in this way, Sartre both popularized it as something that had philosophical substance and defined it out of relevance as an intermediate step on the path to a post-racial future.

Sanghor responded to Satre but not with a full repudiation, but rather with a specific objection to the claim that racial experience was merely subjective. For Senghor. Négritude was a realized real universal realizable experience common to Black people everywhere. He and others defended this by fleshing out a philosophy of Négritude, which codified ontology, epistemology, aesthetics, and political philosophy that we'll look at in a few.

NÉGRITUDE THE PHILOSOPHY

Négritude is a philosophical, poetic, and political movement most closely associated with Leopold Sedar Senghor, Aime Cesaire, and Leon Gontron Damas. Cesaire and Damas viewed Négritude more as a poetic movement while Senghor enunciated more philosophical content of the movement. Though Cesaire enunciated some content as well.

Belgian philosopher, Leo Apostel summarized Senghor's Négritude ontology of life force with seven principles. These seven principles were that:

1. Existence is equivalent to life force, only if one is a force. Each force is unique and individual.

2. They're not part of a single greater force (kind of that questionable one in the many we might see in very early philosophy.)

3. Different things have different types and intensities of forces.

4. Forces can be reinforced, added to, or deforced

5. Weakened forces can act upon each other.

6. All forces are organized into a hierarchy by strength with God at the top, and

7. Stronger forces act upon weaker forces.

So this is an ontology of life forces. This idea exists in people’s life forces that organize them into a hierarchy that can be weakened, can be strengthened, et cetera.

Now, for Senghor, a uniquely African philosophy of art was essential to the Négritude movement. Senghor made the case that the goal of African art was not to represent reality as it was, but rather to represent sub-reality, the world of these forces that were described in his ontology. The purpose of the art was not to give visually perfect or create accurate representations of things as they were, but rather things as the forces within them represented them. This is why African objects of art were not merely aesthetic objects, but religious ones as well, and also why they over-emphasize and under-emphasized certain characteristics, because they're emphasizing elements essential to the life forces not attempting to create a visual facsimile representing not what was observable, but he underlying forces. Senghor made the case that these life forces were kinds of rhythms that were alive and free, not bound to specific conventions, but rather illuminating the spirit.

Cesaire's expression of an aesthetics of Négritude did not differ from Senghor's as they did in the ontology, but rather approached it from a different direction. Cesaire uses Nietzsche's distinction between Dionysian art, which speaks to emotions by representing more primal, obscure, rhythmic forces that fit the object into a web of life and life forces, and Apollonian art, which speaks to the mind by creating more meticulous, artificial representations that divorced an individual work from its surroundings and separated and set it apart, to frame the conversation.

For Cesaire, traditional Western aesthetics had gotten to a point of overemphasizing the Apollonian tradition at the expense of the Dionysian and an aesthetics of Négritude would not overemphasize necessarily the Dionysian side, but rather balance the two better, including more of that primal rhythmic life force within the art, as opposed to the static, almost mathematical pure form of the Apollonian tradition, and tying a piece of work more into the world around it as opposed to trying to set it aside or separate it from the world in a world of form.

Négritude as a movement was decidedly Marxist, though Cesar and Senghor rejected mainstream socialism to varying degrees. Their central concern was with the view expressed by Sartre in the previous video, that race was simply a subjective concrete particular compared to the universal abstract of a class. Cesaire argued that this thin universalism failed to address the specific needs and experiences of African people, and that there were dangers in excessive universalization as well. Négritude therefore attempted to construct a uniquely African socialism based around pre-colonial communitarian societies. They focused on the early works of Marx, where his focus was much more on ethics, art, and humanism, and less on economics.

MeWeFree is proud to honor the vision of Senghor, Césaire, and Damas. We also embrace the modern understanding of Négritude as “the quality or fact of being of Black African origin” and “the affirmation or consciousness of the value of Black or African culture, heritage, and identity.” We boil it down even further to define it ourselves as “the state of being Black.” In this spirit, MeWeFree wields the philosophy of Négritude on behalf of the global Black community, rejecting the divisive and harmful “Diaspora Wars” that erupt on social media. Instead, we champion unity, celebrating the richness of Black cultures around the world while creating space for healing, pride, and connection.